While Indians have had a long history in philanthropy, the space has not been organized. However this is changing, probably not co-incidentally, with the transfer of wealth to the younger generation which is more technologically savvy and wants more transparency.

Philanthropy has a deep and broad foundation in Indian society, though it’s only recently being included in discussions with the wealth management industry. This could be driven by the newer generation of clients who require help with selecting charities and wanting more transparency in measuring impact. It’s also being driven by the wealth industry to deepen its relationship with clients.

Philanthropy can be the glue that keeps a family together over the generations in circumstances where common investment of funds or even the joint ownership of a family business would not.

Philanthropy is getting more organised

While Indians have always shown a very strong commitment to supporting their extended family and community, their philanthropic work hasn’t been recorded in an organized way, beyond some well-known examples. A number of recent reports have attempted to fill this gap – Bain & Co publishes an annual Indian Philanthropy Report, while UBS and London School of Economics India Observatory released a book called ‘Revealing Indian Philanthropy’. The India Giving Report by Charities Aid Foundation attempted to understand donor behavior across the general public. And in early 2012 the Indian government’s Central Statistics Office concluded a four-year study, Non- Profit Institutions in India, to measure the broader non-profit sector.

The CSO report revealed the non-profit sector could be as large as US$ 60bn and includes over 15 million volunteers accounting for over 85% of the sector workforce. It also indicated that giving is becoming more formalized, with over 70% of societies registered in 2008 having been set up after 1990. UBS’s analysis revealed a similar pattern with the vast majority of trusts and foundations set up by the current generation of billionaires having been set up after 1990.

Research conducted by Wealth-X also showed that the top 10 Indian philanthropists gave away from US$2billion, largely by transferring large shares of their wealth to set up endowed foundations.

Organisations like Dasra, Samhita, Give India help people with research on NGOs, and formalize their giving programs.

Dasra prepares research reports on particular themes such as domestic violence, anti sex trafficking or toilets and sanitation, spending 6-9 months evaluating over 200 entities. The reports help with understanding which intervention is creating the most value. The team then spends time with those management teams to see if they have plans of scale and reaching out to a larger community, proving their process continually and then two or three out of 200 entities are chosen to pitch their models to raise funding.

Dasra then brings together approximately 10 people into a ‘Giving Circle’ to collaborate in not only pooling capital but to hear the presentations of the two or three entities and then choose one. The benefit is that each member provides INR 30 lakhs (US$ 50,000 at US$1 = INR 60) of funding over a three-year period. So about INR 3 crore (~US$ 500,000) worth of funding is gathered for a single organization.

Dasra’s involvement continues in the form of 100 days of support per year for three years. Explains Dasra’s partner and co-founder, Deval Sanghvi, “we capacity build them to have stronger plans in place because most non-profits are so busy running day to day operations. Similar to most start-up entrepreneurs, they don’t have the ability to actually take a step back and have a perspective to look at a 3-5 year plan.”

Similarly, Samhita is another organization that researches a sector or cause, including the macro issues, and identifies two or three high impact interventions. It then works with individuals, foundations and orporate to provide customized advice on which NGOs would fit their purpose.

Adds Priya Naik, founder and joint managing director, Samhita Social Ventures, the emergence such organisations is part of the philanthropy sector getting more organized. “There is a planned and unplanned approach. People are now asking themselves about whether they are willing to take a long term approach or is it just let’s give some money and see how it goes.”

Naik wasn’t sure whether the trend to more organized philanthropy was because of the sample – the people Samhita engages with have usually already decided to get more organized. She summarises the trend as “Older generation used to practice responsive philanthropy. People would come to them and they would figure out whom they want to support. The shift we are seeing is that philanthropists are more comfortable in going out, and figuring out which are the right organizations they want to support. This is huge mindset shift.

Focus changing from infrastructure to meaningful impact

Naik divides the universe into two kinds of people. “There are people who have been giving, and over time have developed a point of view for what works for them. And then there are those who haven’t given at all and want guidance,” she says. She sees a lot more philanthropists moving from just writing a cheque to moving to a sustainable model where they support organizational development.

Another trend that Naik identified is that philanthropists are thinking a lot more in terms of sustainability. They ask themselves questions like “how long are we going to engage with the organisation? Can we change focus from program implementation to organizational development? Can we look for partners rather than just beneficiaries?”

Dasra’s Sanghvi agrees and comments that majority of funding still goes to education programs. “There is an inherent belief amongst philanthropists that education is the easiest way out of poverty. The issue with that is that many of the same philanthropists don’t realise that it’s a long term commitment that they need to make. “

He points out that a lot of people focus on education thinking they will start a school, not realizing it’s actually a 12-year commitment to just schooling, after which there is college and actual livelihood opportunities. “Unfortunately people are gung-ho about focusing on education but they don’t necessarily make the 12-15 year commitment to begin with even to put one class of children through the class much less the longer term commitment of ensuring that the school outlives the founder which in essence is required for high quality education to prevail in this country.”

Sanghvi suggests the need is not in the education infrastructure, but in competent teachers working within the school infrastructure that the government provides. So Dasra formed a ‘giving circle’ to fund a teacher training institute in Mumbai enabling slum dwelling women in the community to become trained as English medium teachers and go into these schools that are accessed by slum dwelling children.

“It’s not about building something with your name on it whether it’s a school, hospital or a community centre. Infrastructure the government will provide; it’s what happens within them is where private philanthropy should and will play a role.”

However, the wealthier philanthropists are already thinking beyond education and health sectors. The Revealing Indian Philanthropy book highlights that they have not only identified other causes and feasible solutions, they have demonstrated a willingness to experiment with models, invest in entrepreneurs and share their knowledge for the benefit of all. The causes range from social to political, culture and sport.

According to Revealing Indian Philanthropy, there is a shift in the current generation of philanthropists in that they are thinking big and attempting to etch their legacy on the future of the country. This is in contrast with the attitudes of the previous generations for whom giving was a more personal action with localized impact.

The book highlights that today’s philanthropists are aware of the magnitude of the issues they tackle and realize it is of utmost importance to scale up their programmes if they are to solve systemic problems. Ajay Piramal, chairman of the Piramal Group, is quoted as saying “If an idea cannot be scaled up, it needs to be scrapped.”

The Bain India Philanthropy Report also highlights this difference between conventional and sophisticated donors, saying conventional donors invest in philanthropy for personal, emotional and sometimes religious reasons, while sophisticated donors have clear mandates for creating sustainable and meaningful change in a chosen sector.

The report further points out that conventional donors lean towards projects that reach out to the maximum number of beneficiaries, and they often hold no specific long-term view of the sector or the NGO. That is not the case with sophisticated donors, who are more willing to commit for longer periods to foster systemic change.

And this attitude is not just limited to the really wealthy. Dasra’s approach of the Giving Circle focusing on funding one NGO in a sector, and then helping them scale is a reflection of the desire of philanthropists to have a meaningful impact. Says Sanghvi, “One of the biggest changes we help philanthropists realise is that they should aspire to think bigger. Think about how the INR 30 lakhs can play a catalysing role to raise INR 3 crores worth of funding which ends up creating sector leaders and raising US$ 6.7 million worth of support versus how can my 30 lakhs educate 150 kids over a three year period and end at that. It is a big mind shift that people are still taking a longer time to come to in India whereas in the west that shift has occurred already.”

Sanghvi sums up the utility of his organization by saying, “We have been able to demonstrate that we are not only looking at the floor in terms of the NGO not embezzling money but also more importantly do they have the ability to scale. “

Demand for more governance

The Bain report also highlights another trend – sophisticated donors demand comprehensive assessment and often follow up with regular oversight, such as half-yearly reviews or annual personal visits. They follow a metric-driven decision-making process. Conventional donors, on the other hand, are

more informal and loosely engaged. They do not approach their charitable giving with the same rigour that they may demand of their business or profession.

Most NGOs tend to be satisfied with “activity” metrics, while the sophisticated players follow defined processes to identify, measure and disseminate impact-related data. Their processes stand up to the scrutiny of the most knowledgeable donors and large foundations.

Sanghvi of Dasra “Typically philanthropic decisions are made by ‘who do I trust?’ i.e., the benchmark of my success in my giving is ‘who do I know who is not going to embezzle money?’ If we ran our business decisions in that manner we would make zero return on investment. We would just be happy that people are not embezzling. For Dasra we care about impact and in order to care about impact of course governance is important but that’s the floor of our approach and not the ceiling.”

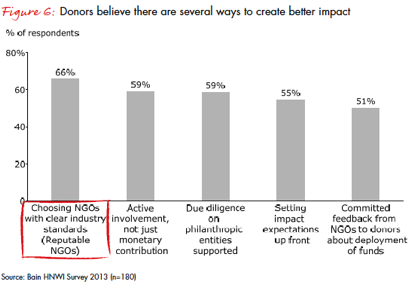

To spur philanthropic contributions, it is crucial that impact becomes a central part of the conversation between donors and NGOs. Such efforts will not only increase confidence among the donor community in the value of their contributions, but they will also squeeze out the maximum efficiency of each philanthropic rupee. In addition, Bain’s survey of HNWIs reveals that validating impacts alone may encourage donors to hike up their philanthropic giving. About two-thirds of the donors surveyed currently believe that NGOs have room to improve the impact they are making in the lives of beneficiaries. If NGOs could step up their game to improve their impact creation and communication, however, the survey finds that 26% of donors would increase their philanthropic contributions

Organised philanthropy as a way of leaving a legacy is also much more accepted today than in previous years. The on- going financial crisis has led to some tightening of purse strings and more importantly to a greater scrutiny of grant- making.

The Bain report suggests some best practices that can amplify the impact of every philanthropic rupee invested. Apart from conducting a rigorous due diligence of the organisations they support, donors can get a bigger bang for their buck by setting expectations about impact at the start of the funding process. In addition, donors believe they can encourage better accountability by directing funds towards NGOs that adhere to industry standards.

Becoming ambassadors

Samhita’s Naik highlighted another trend amongst the current genre of philanthropists – “They seem to be more willing to bring in other individuals. Once they like an idea, they go out and get their friends involved. In the younger generation we see a desire to get more involved, almost build a legacy and build a long term program instead of just writing a cheque.”

She mentioned that people like Luis Miranda are not only donors themselves, but once they identify a cause, they go out and engage their friends. They might even become trustees of the organization they support.

So it is important to ask potential donors about their level of involvement. Some people prefer giving on a personal basis, while others get the whole family involved. Some people have strong views on particular causes so do they want to implement their point of view or are they happy supporting someone else doing it? And lastly, do they want to be passive donors or do they want to catalytic approach? Are they ambassadors?

You must be logged in to post a comment.