Consumer protection takes more than transparency

The principles of transparency and disclosure are visible everywhere from fast-food menus to financial regulation. But if lawmakers don’t consider the behavior of both markets and consumers, better information may not translate to smarter shoppers.

An educated consumer is our best customer.” So insisted the US off-price clothing chain SYMS for more than three decades—before consumers, educated and otherwise, saw the company file for bankruptcy in 2011.

Whether or not educated consumers are reliable friends to business, improving consumers’ access to information may at least make them more likely to act in their own best interest. “Full disclosure” and “transparency” have become mantras among regulators and consumer advocates, who argue that if consumers have complete product information, they can make more-informed, economical purchases.

Disclosure and transparency are at the heart of many countries’ securities regulations, campaign-finance laws, and corporate-governance initiatives. They’re also behind local and federal efforts to compel restaurants to reveal the calorie counts of menu items and force pharmaceutical companies to advertise potential side effects of certain drugs.

But some researchers find that increasingly, businesses and regulators are reaching the limits of transparency, either because consumers aren’t getting the message or are misinterpreting it, or because the market itself prevents consumers from fully acting on the information they receive. “Disclosure alone doesn’t always have beneficial effects,” says Chicago Booth’s Oleg Urminsky. “I don’t think disclosure is a cure-all.”

In three studies supported by Chicago Booth’s Initiative on Global Markets, researchers discovered that how people react to disclosure depends not only on the information they receive, but how they receive it and what, if any, limitations they face in using it. But disclosure doesn’t just affect customer behavior; some of the studies also find evidence that when they’re forced to be transparent, businesses make other adjustments as well, adding further complexity to the question of disclosure’s real effects.

When calories don’t count

Public-health officials have traditionally viewed calorie labeling as a tool in the battle against obesity, whose prevalence in the United States nearly tripled between the early 1960s and 2010, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Letting consumers know what they’re eating, the thinking goes, encourages them to consume healthier food with fewer calories. But the evidence of calorie labeling’s ability to actually influence behavior is mixed and inconsistent.

A well-known 2010 study of Starbucks stores in New York City, which requires chains to post calorie counts, reported a 6 percent decrease in food calories consumed, though there was no change in beverage purchases. A 2011 review of literature concluded that “calorie labeling does not have the intended effect of decreasing calorie purchasing or consumption.”

Urminsky, along with recent Chicago Booth PhD recipient Indranil Goswami, wanted to find out why. They conducted three studies with more than 2,000 adult participants, who were either visitors to a Chicago-area museum or online survey respondents. The researchers offered their test subjects choices among various packaged foods, with some subjects seeing packages with no nutritional labeling, and others seeing labels of varying size and content.

Because each label format displayed nutritional information differently, Urminsky and Goswami could test which elements of nutritional labels had a stronger effect on consumer choice. But the researchers also gave some subjects what they describe as “mere reminders”—prompts to help them remember the importance of eating healthier food with fewer calories without providing additional information.

Food for thought

When asked to pick a chicken sandwich, study participants chose the lowest-calorie option if calorie counts were presented prominently. But simply reminding people to consider nutrition also inspired healthier choices.

Urminsky and Goswami find that “visually salient” calorie labels—those featuring the calorie count prominently, such as by using bigger fonts or bright-red lettering—“are more effective in reducing calorie choices than standard industry disclosures.” But so were noninformative “mere reminders.”

“Our argument is that mere disclosure—such as sticking calorie count in a small spot somewhere on the package—most of the time is not going to have much of an effect,” Urminsky explains. “Putting it in in a really noticeable way is likely to have a pretty substantial effect.”

But the effective labeling “works primarily as a reminder, prompting people to consider nutrition, rather than by providing new information.”

It’s a subtle but important distinction, says Urminsky.

“A main part of that effect—we estimate about two-thirds—is going to be determined not by the fact that you got through to them the information you were trying to convey about calories, but . . . by reminding them, ‘Hey, when you make your decision, please think about calories.’”

That goes beyond the cornerstone of “trans-parency” thinking—that if you give consumers the right information, they’ll make decisions that will benefit their health and welfare. Study subjects were influenced less by the specific content of the information than by being made conscious of calories and their consequences. In fact, in some cases, when consumers’ beliefs about nutrition differed from actual calorie content, they tended to follow their beliefs and ignore the facts.

Urminsky suggests that making calorie labels more prominent and readable will go a long way to addressing some of their shortcomings. But he thinks researchers and policy makers need to better understand how labeling actually affects consumers.

“I think it’s worth having a conversation that asks, ‘If we’re ramping up the font size of the calorie information, what is that doing?’” he says. “Is it just making us more effective at conveying information, or is it also going beyond purely conveying information to actually have a reminder or implied prescriptive component as well?”

“The way in which you give people information could convey a recommendation,” he says, “but even if it doesn’t convey a recommendation, it affects how we think.”

Roadside attractions

Roadside signs are another form of labeling. They can prompt motorists to fasten their seat belts, pay attention to roadwork ahead, or patronize nearby merchants or shopping centers.

In 2007, the Italian parliament began requiring gasoline retailers located near Italy’s Autostrade, the highway system that traverses the country, to post their prices on electronic signs along the motorway and update them as they change. Each sign shows the price of gasoline charged by several nearby service stations, allowing drivers to comparison shop for gas.

The goal: increase price transparency for the benefit of drivers, and also promote competition.

Chicago Booth’s Pradeep K. Chintagunta and Federico Rossi of Bocconi University in Milan studied what happened to gas prices between October 2008 and May 2009. Gasoline is a commodity, and Chintagunta explains that “in circumstances where the products are, in fact, identical, then it makes sense to say the more information the consumer has, the better off the consumer will be.”

Prices charged by gas stations near the Autostrade did indeed decrease—by 1 euro cent per liter, equivalent to 20 percent of the stations’ margins. However, the policy was most effective for service stations only a short distance from the signs.

Furthermore, only a small group of frequent shoppers—fewer than 10 percent of all the consumers, according to the researchers’ estimates—seemed to use the price information available to choose the stations with the lowest prices.

Some logistical complications may be to blame. “Although you’re providing these signs, it’s not clear you’re getting the full benefit for a couple of reasons,” Chintagunta explains. “One is people are driving too fast and can’t read the prices, and a second is, keep in mind, people are entering and exiting the highway in between the signs and so are missing these signs. For these people, you are not going to see much of an effect, because they are not exposed to these signs at all.”

The research suggests that to give the public the maximum benefit of greater transparency, policy makers have to consider not only what information consumers receive but how—and if—they’ll be able to put it to use.

Shopping for surgeries

Health care is a highly complex industry, making up about 18 percent of US GDP. It encompasses hospital emergency rooms, nursing homes, highly trained specialists, and elective procedures such as

cosmetic surgery.

But despite—or perhaps because of—its complexity, it too has become a market where regulators have pushed for greater price transparency, and where researchers are examining how disclosure can affect consumer behavior.

Hans B. Christensen and Mark G. Maffett of Chicago Booth and Eric Floyd of Rice University focused on regulations adopted by 27 US states that require hospitals to disclose pricing on publicly visible state websites, allowing patients to compare the average charges for common procedures across hospitals within the state.

They studied five procedures, some elective and some urgent: cesarean sections, knee replacements, hip replacements, appendectomies, and uterine procedures. Using data from MarketScan and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, they examined both hospital charges (the prices hospitals initially bill) and actual payments (the price patients ultimately pay) for these procedures made by privately insured and self-paying patients.

Several features of the health-care market made it distinct from, say, gasoline stations on the Autostrade, which sell a commodity at nearly identical prices.

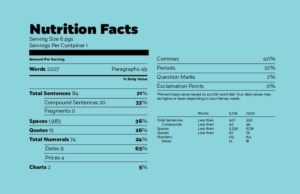

First, there was wide price dispersion for identical procedures. In the sample the researchers studied, the cost of appendectomies ranged from $6,652 to $68,509.

Second, only 12 percent of US health-care payments in 2013 were made by consumers; the government and private insurers paid more than 80 percent. Except for elective procedures, consumers’ expenditures typically comprise co-payments and deductibles rather than full out-of-pocket payment to health-care providers. Since consumers generally don’t pay directly, they have less incentive to shop for the lowest price, Christensen says.

Third, patients often choose hospitals based on where their physicians have admitting privileges, so to some degree, physicians become the gatekeepers.

Finally, during medical emergencies, patients have little time or incentive to shop around for the most economical hospital or provider.

After controlling for some of the US health-care market’s quirks, Christensen, Maffett, and Floyd still are able to document a 6.4 percent decrease in charges for disclosed procedures in those states that implemented transparency regulation. But these charge reductions did not lead to declines in actual prices. In fact, the drop in charges wasn’t due to patients’ comparison shopping. “The bulk of the observed reduction in charges is attributable to hospitals reducing their prices rather than patients switching to cheaper hospitals,” they write.

Same procedures, but very different prices

Twenty-seven states require hospitals to disclose pricing on publicly visible state websites. But there is still a wide variation in the prices charged in those states for hospital procedures.

The hospitals that tended to reduce prices the most were those that charged the most before they had to post their prices. So, the hospitals that charged $68,000 for appendectomies were more likely to cut their prices than the ones that charged $6,000.

The researchers discovered that the biggest decline in charges came from not-for-profit hospitals and those that served large lower-income populations, “where reputational costs of perceived overcharging are likely the highest.” No hospital wants to be known for gouging the poor.

Providers were cutting prices more because of what competitors were doing than because of what consumers were demanding. And yet, because of the unusual price structure in health care, hospitals could accommodate price cuts by reducing discounts to insurers and other contracted third-party providers and thus, in the words of the researchers, “avoid passing these charge reductions on to patients” and “mitigate reputational costs without sacrificing profits.”

“If you look only at these charged prices, then you may well conclude that the regulation works because the intention was to lower prices, and now people can shop around for lower prices,” says Christensen. “But what we really find is there is probably no social benefit, because they’re able to offset [the lower prices with discounts].”

Transparency, he continues, “is a broad policy instrument that has been used in many, many places. What we’re trying to say is that it is not obvious that it works everywhere, and this illustrates that, to some extent, because this is just a very different market.

“You need to consider the specific incentives and structures of the market when you design this. The high-level takeaway is, you have to consider the underlying incentives before you can decide whether [transparency] works or not.”

Like the studies of calorie labeling and the Autostrade, Christensen, Maffett, and Floyd’s work underscores the practical limitations of disclosure. However laudable a goal transparency may be, in the real world, it works imperfectly and doesn’t always translate directly into smarter consumer decisions.

Collectively, the research demonstrates that politicians and regulators have to carefully consider where and how to push for greater transparency if they hope to make it an engine for greater consumer welfare.

—–

Works cited

Bryan Bollinger, Phillip Leslie, and Alan Sorensen, “Calorie Posting in Chain Restaurants,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, American Economic Association, February 2011.

Pradeep K. Chintagunta and Federico Rossi, “Price Transparency and Retail Prices,” Working paper, January 2015.

Hans B. Christensen, Eric Floyd, and Mark G. Maffett, “The Effects of Price Transparency on Prices in the Healthcare Industry,” Working paper, October 2013.

Indranil Goswami and Oleg Urminsky, “The ‘Mere Reminder’ Effect of Salient Calorie Labeling,” Working paper, January 2015.

Jonas J. Swarz, Danielle Braxton, and Anthony J. Viera, “Calorie Labeling on Quick-Service Restaurant Menus: An Updated Systematic Review of the Literature,”International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, December 2011.

——-

This article originally appeared in Capital Ideas, a publication of the University of Chicago (http://www.chicagobooth.edu/capideas)

You must be logged in to post a comment.